Eva Visits Noriko-San

I was never happier about any Children of the World book. This book, almost impossible to track down, was the best possible book to finish the series on. It’s ridiculously cute. The copy I have has 50% ripped pages, taped together and yellowed with age. It’s original title was Eva moter Noriko-San, published in 1956.

I was never happier about any Children of the World book. This book, almost impossible to track down, was the best possible book to finish the series on. It’s ridiculously cute. The copy I have has 50% ripped pages, taped together and yellowed with age. It’s original title was Eva moter Noriko-San, published in 1956.

Eva gets the news that she is going to visit Noriko-San all by herself (!). Noriko-San gets ready for her, putting on a kimono and arranging a bunch of super-creepy dolls. Eva comes and the two frolic about. They switch outfits. Finally Eva leaves. From the plane window she waves with her hankie. I giggled.

I don’t really understand why this is the most rare Astrid Lindgren book of all; it’s cute, but this book seems like it has a following like no other book in the series.

You have to suspend your belief in reality a little for this book: Then all at once, the smallest cousin of all says, “Listen. I hear an airplane.” And that was really Eva’s plane.

This book claims to be part of the “Children of the World” series. Whew. That is so much better than “Children’s Everywhere.” No other book in the series so far has claimed “Children of the World,” but I am going to run with it.

This book claims to be part of the “Children of the World” series. Whew. That is so much better than “Children’s Everywhere.” No other book in the series so far has claimed “Children of the World,” but I am going to run with it. Here, almost at the end of the Children of the World series, I am presented with a (relative) gem of a story. Noy Lives in Thailand is listed on Astrid Lindgren’s website (and also Wikipedia) as Noby Lives in Thailand, but the original Swedish version of 1966 was titled Noy bor i Thailand and the English version is about Noy as well, so an online typographical error seems like the most likely situation. I doubt a book about Noby ever existed – if it did, Google can’t find it.

Here, almost at the end of the Children of the World series, I am presented with a (relative) gem of a story. Noy Lives in Thailand is listed on Astrid Lindgren’s website (and also Wikipedia) as Noby Lives in Thailand, but the original Swedish version of 1966 was titled Noy bor i Thailand and the English version is about Noy as well, so an online typographical error seems like the most likely situation. I doubt a book about Noby ever existed – if it did, Google can’t find it. Lilibet, Circus Child (listed as simply Circus Child on some Lindgren websites) tells the story of young Lilibet who grows up in a circus (bet you didn’t see that one coming). The original title was Lilibet Cirkusbarn and it was published in Sweden in 1960. Translators for this series are unknown.

Lilibet, Circus Child (listed as simply Circus Child on some Lindgren websites) tells the story of young Lilibet who grows up in a circus (bet you didn’t see that one coming). The original title was Lilibet Cirkusbarn and it was published in Sweden in 1960. Translators for this series are unknown. My Swedish Cousins was originally Mina svenska kusiner (1959). As with all books in this series so far, the translator remains a mystery. Probably had to join the Swedish version of the witness protection program.

My Swedish Cousins was originally Mina svenska kusiner (1959). As with all books in this series so far, the translator remains a mystery. Probably had to join the Swedish version of the witness protection program. In Dirk Lives in Holland, we continue the Riwkin-Brick series “Children’s Everywhere.” The Swedish title, Jackie Lives in Holland (1963) was translated by someone, but it’s just as well we don’t know who. Whoever it was did a terrible job. Not knowing Swedish, how can I tell that he or she did an awful job? Because part way through the book, Dirk is referred to as “Jackie.” Anyone reading it, without knowing the original title, would be completely and utterly lost.

In Dirk Lives in Holland, we continue the Riwkin-Brick series “Children’s Everywhere.” The Swedish title, Jackie Lives in Holland (1963) was translated by someone, but it’s just as well we don’t know who. Whoever it was did a terrible job. Not knowing Swedish, how can I tell that he or she did an awful job? Because part way through the book, Dirk is referred to as “Jackie.” Anyone reading it, without knowing the original title, would be completely and utterly lost. Randi Lives in Norway was originally Gerda Lives in Norway in the Swedish version (1965). Why the need to change this name? This might be worse than Rasmus/Eric. I could ask the translator if a translator was listed, but of course, none is.

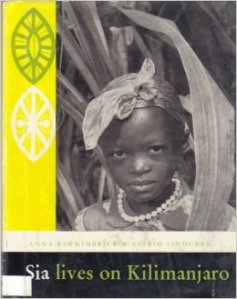

Randi Lives in Norway was originally Gerda Lives in Norway in the Swedish version (1965). Why the need to change this name? This might be worse than Rasmus/Eric. I could ask the translator if a translator was listed, but of course, none is. text to accompany her photographs, Lindgren wrote it, beginning a long collaboration. As far as I can tell, they worked together on nine books in total, although this series is very difficult to find information about.

text to accompany her photographs, Lindgren wrote it, beginning a long collaboration. As far as I can tell, they worked together on nine books in total, although this series is very difficult to find information about.